If you’ve ever looked in the mirror and seen a pink, fleshy wedge growing from the white of your eye toward your pupil, you’re not alone. This isn’t a rash, an infection, or something you caught from someone else. It’s pterygium - often called "Surfer’s Eye" - and it’s caused by one thing: too much sun.

Unlike a cataract that clouds the lens, or glaucoma that damages the optic nerve, pterygium grows right on the surface of your eye. It starts on the conjunctiva, the clear tissue covering the white part, and slowly creeps onto the cornea - the clear dome in front of your iris. When it reaches the center of your vision, it can blur your sight, make your eye feel gritty, and turn contact lenses into a nightmare.

Why the Sun Is the Main Culprit

It’s not just being outside. It’s being outside without protection. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the number one trigger. People who live near the equator, work outdoors, or spend hours on water, snow, or sand are at highest risk. Studies show that those living within 30 degrees of the equator are 2.3 times more likely to develop pterygium than people in northern latitudes.

And it’s not just about sunny days. UV rays bounce off water, sand, and even snow. A day on the beach or on a boat without sunglasses can add up. One study found that people with more than 15,000 joules per square meter of cumulative UV exposure had a 78% higher chance of developing pterygium. That’s roughly 10 years of daily outdoor exposure without eye protection.

Men are more commonly affected than women - about 3 to 2. That’s likely because more men work in construction, fishing, farming, and other outdoor jobs. Australia has the highest rates in the world, with nearly 23% of adults over 40 affected. In the U.S., rates climb in southern states like Florida and Texas, where UV levels stay high year-round.

What It Looks Like and How It’s Diagnosed

Pterygium usually shows up on the inner corner of the eye - the side closest to your nose. In 95% of cases, it starts there. It looks like a triangular, slightly raised bump with visible tiny blood vessels. Early on, it might be barely noticeable - just a small pink patch. But over time, it can grow 0.5 to 2 millimeters per year under constant UV exposure.

Doctors don’t need scans or blood tests. A simple slit-lamp exam - a bright, magnified light used in eye clinics - is all it takes. The device lets the doctor see exactly how far the growth has moved onto the cornea. If it’s creeping toward the pupil, that’s when vision problems start. It can flatten the cornea’s natural curve, causing astigmatism. That means straight lines look wavy, and reading becomes harder.

It’s easy to confuse pterygium with pinguecula - another sun-related eye growth. But pinguecula stays on the white part of the eye. It never crosses onto the cornea. If it does, it’s officially a pterygium. About 70% of outdoor workers in tropical areas get pinguecula. Only 30% develop pterygium. The difference? Distance from the cornea.

Surgery Isn’t Always Needed - But When Is It?

Most people don’t need surgery. If your pterygium is small, doesn’t bother you, and isn’t growing, your doctor will likely just monitor it. The goal is to stop it from getting worse. That means:

- Wearing UV-blocking sunglasses every day - even on cloudy days

- Using a wide-brimmed hat when outside

- Using preservative-free artificial tears if your eye feels dry or irritated

Research shows that people who wear proper sunglasses daily can stop their pterygium from growing. One Reddit user, "OutdoorPhotog," reported that after switching to UV-blocking shades, his growth didn’t change in two annual check-ups.

Surgery becomes necessary when:

- The growth is blocking your vision

- You can’t wear contact lenses anymore

- Your eye is constantly red, swollen, or painful

- It’s cosmetically disturbing - you feel self-conscious about how it looks

There’s no medication that makes pterygium disappear. Eye drops might ease irritation, but they won’t shrink it. Only surgery can remove it.

The Three Main Surgical Options

Not all surgeries are the same. The technique your surgeon uses affects how likely the pterygium is to come back.

1. Simple Excision (Old Method)

This is just cutting out the growth. It’s quick - under 30 minutes - and done under local anesthesia. But here’s the catch: without anything else, the recurrence rate is 30% to 40%. That means 3 or 4 out of 10 people will get it back within a year or two.

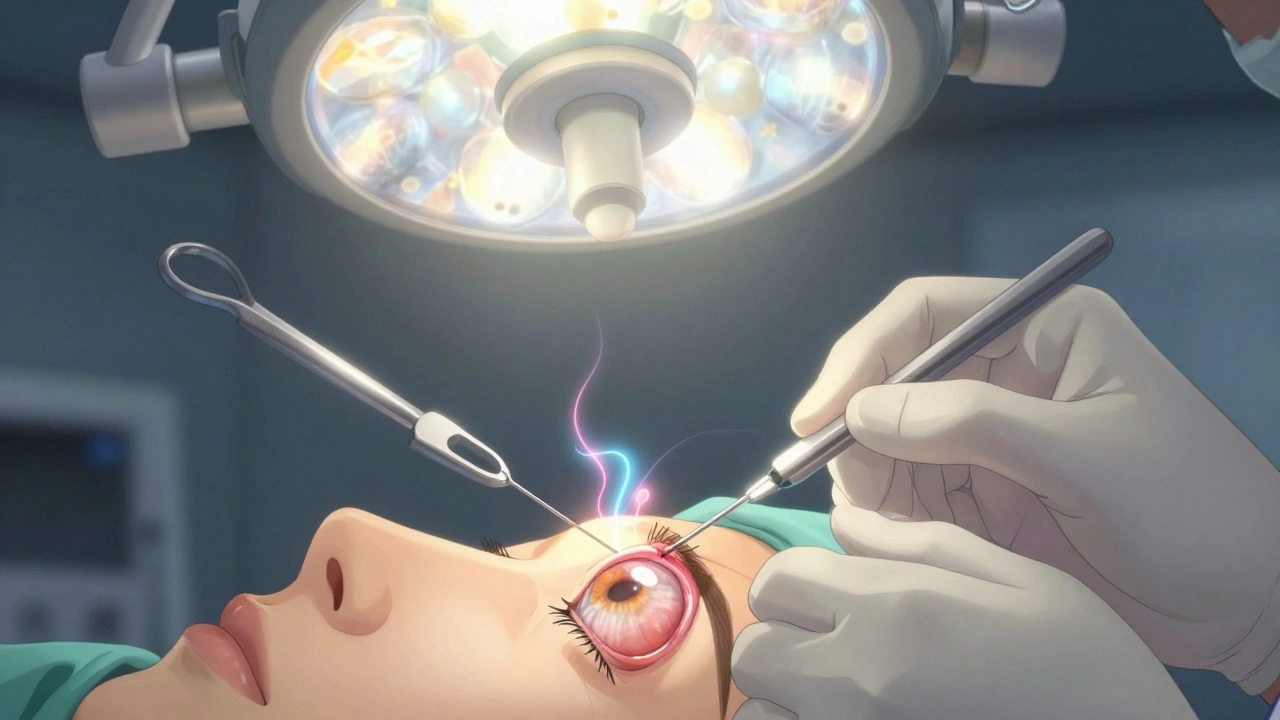

2. Conjunctival Autograft (Gold Standard)

This is now the most common and effective method. After removing the pterygium, the surgeon takes a small piece of healthy conjunctiva from another part of your eye - usually near the top - and stitches it over the empty spot. Think of it like patching a hole with your own tissue.

Why it works: Your own tissue heals better and blocks new growth. Recurrence drops to just 8.7%. This method is used in about 20% of surgeries but has the best long-term results.

3. Mitomycin C + Excision

Mitomycin C is a powerful anti-scarring drug. During surgery, the surgeon applies it directly to the area where the pterygium was removed. It stops the cells from growing back too aggressively.

This combo reduces recurrence to 5-10%. It’s used in about 35% of cases, especially when the pterygium is large or has come back before. But it’s not risk-free. It can cause thinning of the eye surface or delayed healing. That’s why it’s not used for small, early cases.

4. Amniotic Membrane Transplant (Newer Option)

In June 2023, European guidelines started recommending amniotic membrane - tissue from the placenta - as a first-line treatment for recurrent pterygium. It’s not yet common in the U.S., but early results are strong: 92% success rate in preventing regrowth across 15 countries. It’s especially helpful when the eye surface is damaged from previous surgeries.

What to Expect After Surgery

Recovery is usually quick, but not always easy.

- Most people go home the same day.

- Your eye will be red and swollen for 1-2 weeks.

- You’ll need steroid eye drops for 4-6 weeks to reduce inflammation.

- You can’t swim, wear makeup, or rub your eye for at least 2 weeks.

- Full healing takes 2-3 months.

Patients often say they feel immediate relief from grittiness and redness. One patient on RealSelf.com wrote: "The surgery took 35 minutes, but the steroid drops regimen for 6 weeks was more challenging than expected."

Side effects are usually mild: temporary dryness, light sensitivity, or a scratchy feeling. But about 42% of patients report discomfort lasting 2-3 weeks. And 37% say the redness during healing makes them feel self-conscious.

What Happens If You Don’t Treat It?

If you ignore it, three things can happen:

- It grows slowly and never affects vision - you just live with the redness.

- It grows enough to cause astigmatism - your vision gets blurry, and glasses won’t fully fix it.

- It grows over your pupil - now you’re at risk of permanent vision loss.

It doesn’t turn into cancer. But it can steal your sight if left unchecked. And once it’s big, surgery becomes harder and recovery longer.

How to Prevent It - Even If You’re Already at Risk

Prevention is the easiest and cheapest treatment. Here’s what actually works:

- Wear sunglasses labeled "UV400" or "100% UV protection" - not just "dark lenses."

- Choose wraparound styles that block light from the sides.

- Use a wide-brimmed hat (at least 3 inches) every time you’re outside.

- Check the UV index daily. If it’s 3 or higher, protect your eyes.

- Don’t wait until you’re old. Start young. One study found that people who wore UV protection before age 20 had 60% lower risk.

Look for eyewear that meets ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards. That’s the U.S. safety rule requiring lenses to block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays. Cheap sunglasses from a beach stand often don’t meet this.

The Future: What’s Coming Next

Research is moving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved a new eye drop called OcuGel Plus - a preservative-free lubricant designed specifically for post-surgery healing. Patients using it reported 32% more relief than with regular artificial tears.

Even more exciting: Phase II trials are testing a topical cream called rapamycin. Early results show it cuts recurrence by 67% by stopping the cells that cause growth. If approved, this could mean no surgery at all for many patients.

By 2027, 78% of eye surgeons expect to use laser-assisted removal - a less invasive technique that reduces healing time and scarring.

But here’s the problem: access. In rural areas of developing countries, only 12% of people can get surgery. In cities in the U.S. or Europe, it’s 89%. That gap isn’t shrinking fast enough.

Final Takeaway

Pterygium isn’t rare. It’s a direct result of sun exposure - the same sun we love for outdoor life. If you’re active outside, especially near water, sand, or snow, you’re at risk. The good news? You can stop it. Wear sunglasses. Wear a hat. Get your eyes checked yearly.

If you already have it, don’t panic. Most cases don’t need surgery. But if it’s growing or affecting your vision, talk to an ophthalmologist. Surgery works - especially with modern techniques. And if you’ve had it before, ask about amniotic membrane or mitomycin C. Recurrence isn’t inevitable.

Your eyes don’t regenerate. Protect them now - before the growth starts.

Larry Lieberman

December 8, 2025 AT 13:22