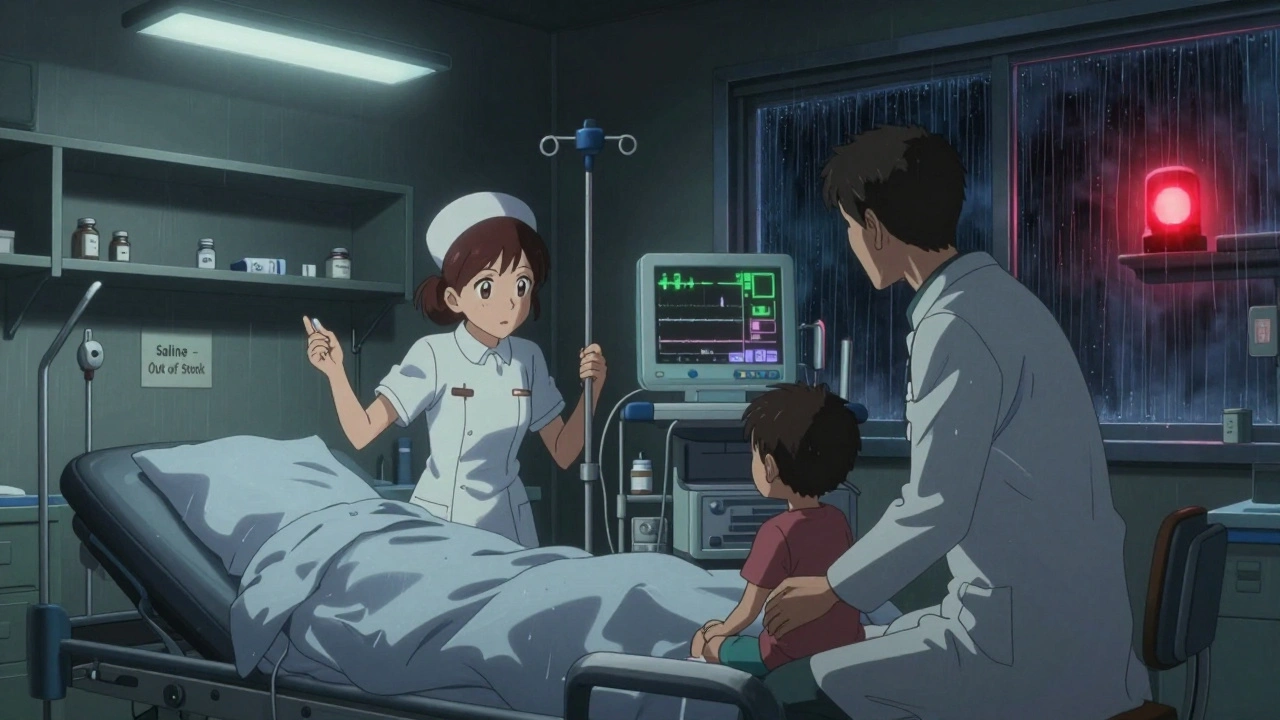

Every year, more than 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. They’re cheaper, widely available, and trusted - or at least they were. Today, that trust is cracking. As of April 2025, there were 270 active drug shortages in the U.S., according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Most of them? Generic medicines. Not brand-name drugs with billion-dollar marketing budgets. Not cutting-edge biologics. But simple, life-saving generics: antibiotics, IV fluids, chemotherapy drugs, epinephrine, heparin. These are the medicines hospitals rely on every day. And they’re disappearing.

Why Generic Drugs Are Falling Through the Cracks

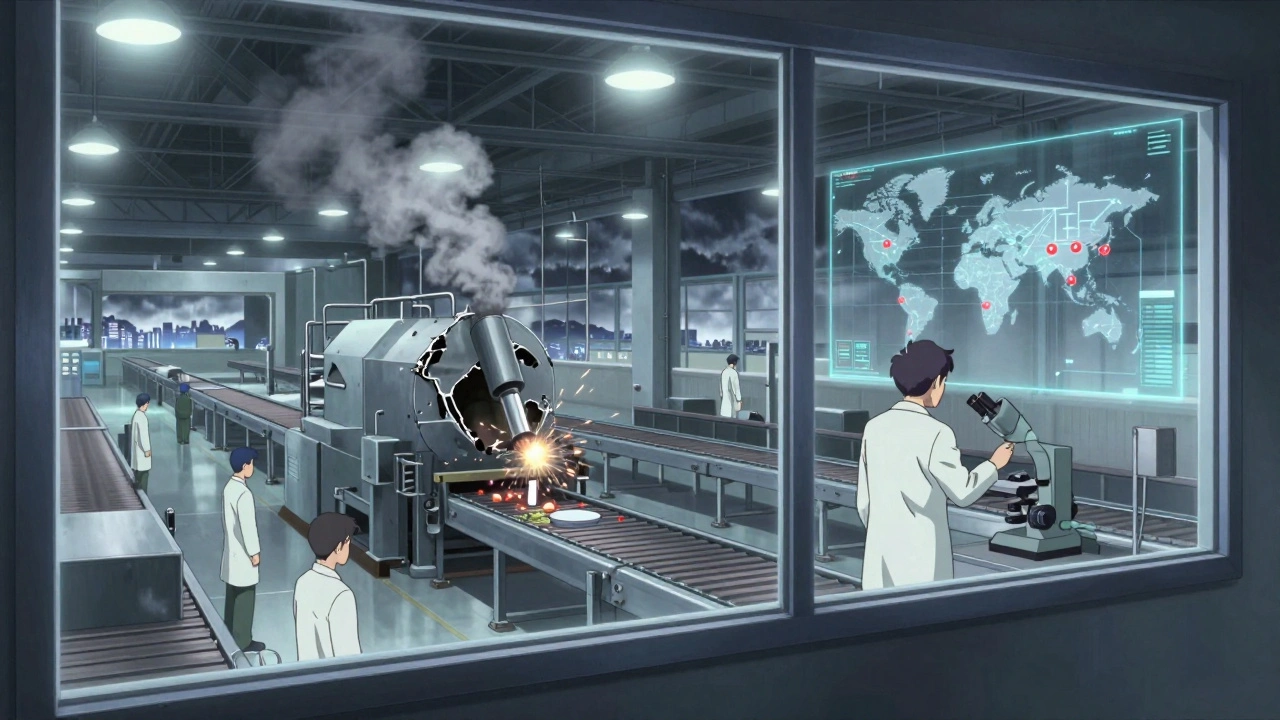

Generic drugs don’t make much money. They cost pennies. A single vial of saline might sell for $1.50. A dose of penicillin? Less than $2. That’s great for patients paying out of pocket. But for manufacturers? It’s a death sentence. With profit margins so thin, companies can’t afford to keep extra inventory. They can’t invest in backup equipment. They can’t afford to build factories in multiple countries. So they concentrate production in just one or two places - usually in China or India. That’s where about 40% of the world’s active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are made. One factory. One machine. One shipment. If something goes wrong, the whole country loses access. In 2023, a tornado ripped through a Pfizer plant in Kentucky. It knocked out production of 15 essential generic drugs overnight. In India, an FDA inspection found quality violations at a facility making cisplatin, a critical chemotherapy drug. Production stopped. The shortage lasted months. Patients delayed treatment. Some skipped doses. Others got substituted with less effective or more toxic alternatives.Sterile Injectables: The Most Fragile Link

Not all generics are created equal. Oral pills are simple to make. You mix powder, press it, bottle it. Sterile injectables? That’s a whole different world. IV bags, injections, chemotherapy drips - these require clean rooms, sterile environments, complex machinery, and highly trained staff. One speck of dust, one contaminated filter, and the entire batch is destroyed. That’s why these drugs are the most common cause of shortages. They’re expensive to produce, hard to scale, and have almost no room for error. The FDA’s 2025 Drug Shortage Report shows that over 60% of active shortages involve sterile injectables. These aren’t luxury drugs. They’re the backbone of emergency care, cancer treatment, and intensive care units. When epinephrine runs out, paramedics can’t treat anaphylaxis. When saline is gone, hospitals can’t hydrate patients or flush IV lines. When heparin disappears, dialysis patients can’t survive.Brand vs. Generic: Two Different Worlds

Compare this to brand-name drug makers. They have global networks. Multiple factories. Stockpiles of raw materials. They spend billions on R&D and charge hundreds or thousands per dose - so they can afford to buffer against disruption. Generic manufacturers don’t have that luxury. They compete on price. The lowest bidder wins the contract. That means no one invests in redundancy. No one builds extra capacity. No one keeps emergency reserves. If a factory in China shuts down for a month, there’s no backup. There’s no Plan B. And it’s getting worse. Market consolidation has turned many generic markets into monopolies. For some older drugs, only one or two companies make them. That’s not competition - that’s a single point of failure. One recall. One inspection failure. One natural disaster. And the entire U.S. supply vanishes.

The China and India Dependency

China supplies about 40% of global APIs. India handles most of the final manufacturing for sterile injectables. Both countries have lower labor costs, less stringent enforcement, and weaker regulatory oversight - at least compared to the U.S. The FDA has documented a long history of unreliable manufacturing practices in these regions. In 2024, inspections at Indian facilities found contamination in 12% of sterile injectable plants. In China, Drug Master File (DMF) submissions - the paperwork required to prove quality - have dropped by 30% since 2020. Why? Because manufacturers are hesitant to apply. They know their practices won’t pass. And yet, the U.S. keeps buying. Why? Because it’s cheaper. But cheap isn’t sustainable when lives are on the line.What Happens When the Drugs Run Out

It’s not just a logistics problem. It’s a patient safety crisis. Pharmacists spend 20-30% of their workweek just trying to find replacements. They scramble to source drugs from overseas distributors. They compound medications in-house - often with limited resources. They ration doses. They switch patients to alternatives that may cause more side effects or require more monitoring. Hospitals report canceled surgeries because they can’t get the anesthetics. Cancer treatments delayed because chemotherapy drugs are unavailable. Emergency rooms turning away patients because they don’t have epinephrine or norepinephrine. In 2024, drug shortages hit a record 323 - the highest ever. And it wasn’t because of the pandemic. It was because the system was already broken. The pandemic just made it visible.

Jimmy Jude

December 5, 2025 AT 00:22