Getting vaccinated while on immunosuppressants isn’t just about when you get the shot-it’s about whether your body can even respond to it. If you’re taking drugs like rituximab, methotrexate, or cyclophosphamide, your immune system is deliberately slowed down. That’s good for managing autoimmune diseases or preventing organ rejection, but it’s a problem when you need your body to build protection from vaccines. The difference between a strong immune response and a weak one often comes down to timing-and getting it wrong can leave you unprotected.

Why Timing Matters More Than You Think

Vaccines work by training your immune system to recognize and fight off viruses or bacteria. But if your immune cells are suppressed by medication, that training doesn’t stick. Studies show people on certain immunosuppressants have up to 70% lower antibody levels after vaccines like flu, COVID-19, or pneumococcal shots. That’s not just a small drop-it means you’re still at risk for serious illness even after being vaccinated. The key is to vaccinate before the drug hits its strongest suppression point. For example, if you’re starting a new biologic like rituximab, which wipes out B-cells for months, you need the vaccine in your system before those cells disappear. Once they’re gone, no amount of later vaccination will fully restore protection. The same goes for drugs like methotrexate, which dulls the immune response every week. Holding it for a couple of weeks around vaccination can make the difference between a strong response and a near-zero one.How Long Should You Wait? The Guidelines Don’t Agree

You might expect doctors to have one clear rule. They don’t. Different organizations give different advice, and it’s confusing even for clinicians. The CDC says to get vaccines at least 14 days before starting immunosuppressants. That’s a baseline, not a guarantee. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) pushes for 2 to 4 weeks before. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) goes even further, with detailed rules for each drug:- Methotrexate: Hold for two weeks after a flu shot if your disease is under control. This one has solid data-three trials showed a 27% increase in antibody production.

- Rituximab: Wait at least 6 months after your last dose before getting non-flu vaccines. Some guidelines say 4 months. Others say 3. The truth? It depends on your B-cell count.

- Biologics like TNF inhibitors: Skip one dose before vaccination and wait 4 weeks after to restart.

- IVIG: If you’re on high doses (1 gram per kg or more), you need to wait 10 months before live vaccines. That’s not a typo-it’s based on how long antibodies from the infusion stick around and block vaccine response.

What About Live Vaccines? The Rules Get Tighter

Live vaccines-like shingles (Shingrix is actually not live, but Zostavax was), MMR, or nasal flu spray-are a whole different ballgame. These contain weakened versions of the virus. If your immune system is too weak, it can’t control them, and you could get sick from the vaccine itself. For live vaccines, most guidelines say: stop immunosuppressants for at least 4 weeks before and after. That means:- If you’re on azathioprine, mycophenolate, or leflunomide, you’ll need to pause them.

- If you’re on intravenous cyclophosphamide, you’ll need to skip one full cycle before and wait 4 weeks after.

Real-World Problems: Missed Doses, Delayed Shots, and Broken Systems

In theory, everyone should get their vaccines timed perfectly. In reality? It’s messy. At Massachusetts General Hospital, 42% of patients on rituximab waited the full 6 months for a shingles vaccine-and 18% of them still got shingles during that time. One patient wrote on a forum: “I waited 6 months. Got shingles. My doctor said it was ‘unavoidable.’ But I felt like I was left to fend for myself.” On the flip side, oncology clinics are doing better. About 78% of cancer patients get their vaccines 2+ weeks before chemo starts, thanks to structured protocols. But for autoimmune patients? Coordination is poor. A 2023 survey found that 47% of primary care doctors couldn’t get clear guidance from rheumatologists or hematologists. So patients get caught in the middle. And then there’s the issue of disparities. A 2022 JAMA Internal Medicine analysis showed Black patients on immunosuppressants had 15-20% lower antibody responses across all vaccine types. The guidelines don’t account for this. We don’t know why-genetics? Access? Social factors? But the outcome is real: more people of color are left unprotected.What’s Changing? The Future Is Personalized

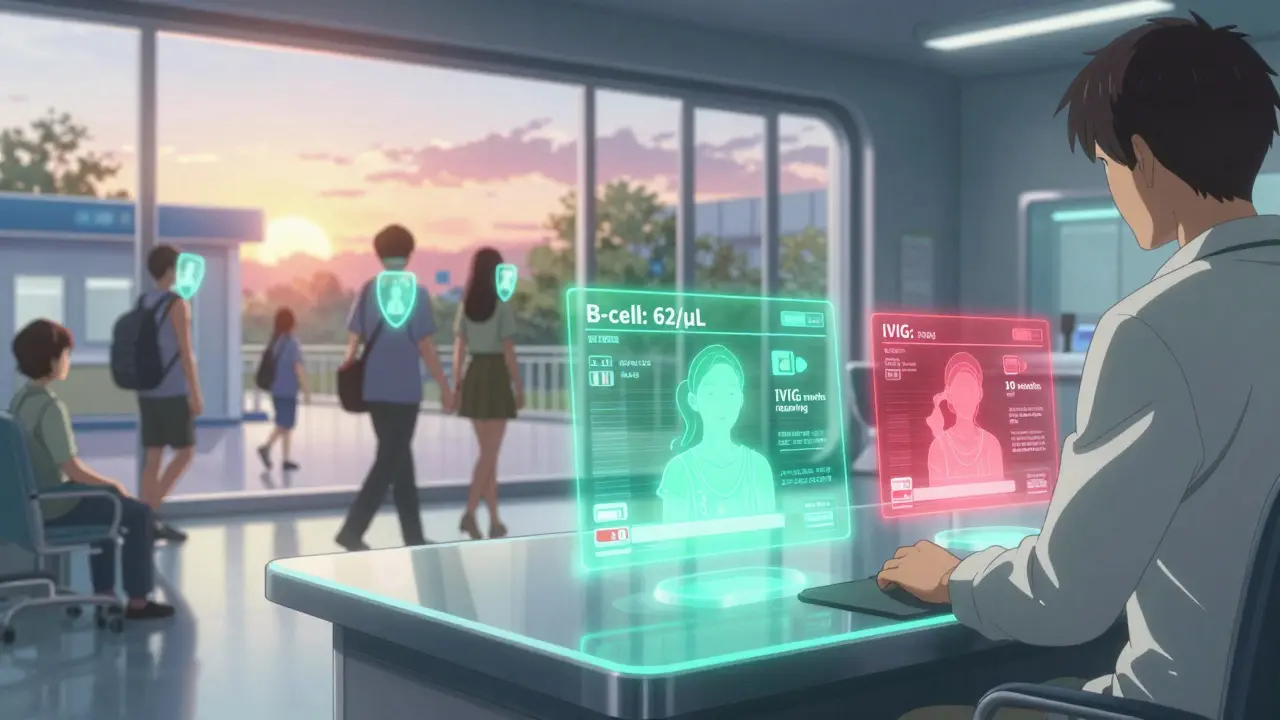

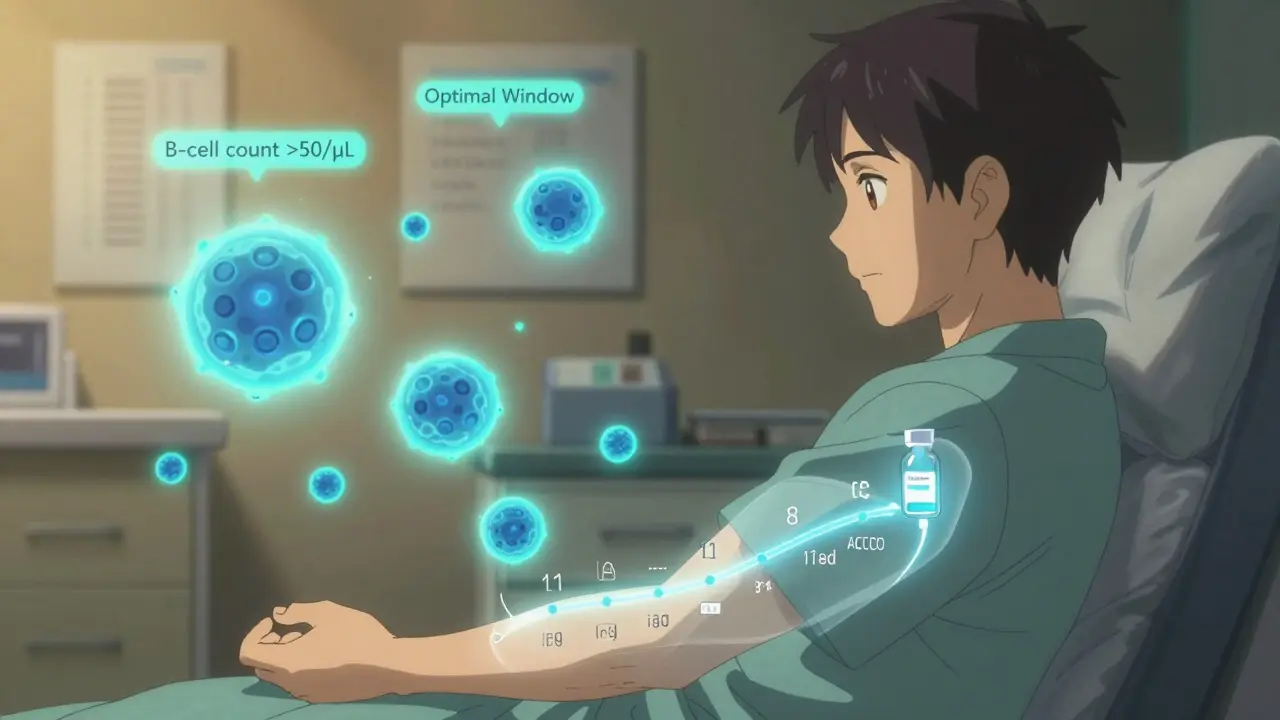

The old way-“wait 6 months”-is fading. The new approach? Measure your immune system. The IDSA 2025 draft guidelines (released in January 2024) now say: don’t just count weeks. Check your B-cell count. If it’s above 50 cells/μL, you’re likely ready for vaccination. That’s a game-changer. One patient in Oregon had B-cells bounce back at 4 months instead of 6. He got his vaccine early-and stayed healthy. The NIH’s VAXIMMUNE study is tracking 2,500 people to see if biomarkers like T-cell activity or antibody levels can predict vaccine success. If it works, we’ll move from fixed schedules to personalized timing-based on your body, not a calendar. And tech is catching up. Epic Systems announced a vaccine timing module for electronic health records, set to launch in 2025. It will automatically flag when a patient is due for a vaccine based on their meds, and suggest the best window. No more manual calculations. No more missed opportunities.

What Should You Do Right Now?

If you’re on immunosuppressants and haven’t had a vaccine conversation with your doctor this year, here’s your checklist:- Know your meds. Not just the names-know if they’re biologics, cell-depleting, or broad immunosuppressants.

- Check your last vaccine. Did you get flu, COVID, shingles, or pneumococcal in the last year? If not, you’re overdue.

- Ask about timing. Don’t say “When should I get my shot?” Say: “Based on my meds, what’s the safest and most effective window?”

- Request a B-cell test (if on rituximab or similar). It’s cheap. It’s simple. And it can save you from waiting 6 months unnecessarily.

- Don’t assume your doctor knows. Many don’t. Bring printed guidelines from ACR or CDC. Ask for a referral to an immunization specialist if needed.

Jonathan Noe

February 14, 2026 AT 14:32